A research paper by the University of Wisconsin entitled “Afghani and Freemasonry in Egypt” researched the role played by secret societies in the political development of modern Egypt. The paper examined the activities of the separatist and political agitator Sayyid Jamal al-Din al-Afghani during his stay in Egypt in the 1870’s (1871-1879), and eventual exile. The document at it’s end reveals that Afghani having kept in close contact with W.S Blunt, in 1885, invited Afghani to come to London to discuss with British officials “the terms of a possible accord between England and Islam”, Afghani supposedly representing Islam.

During a three months’ stay as Blunt’s guest, he met high officials, including Lord Randolph Churchill (a Secretary of State) and Sir Henry Drummond Wolff. The result of these talks was that Afghani should accompany Wolff on a special mission to the Porte “with a view to his exercising his influence with the Pan-Islamic entourage of Sultan Abdu’l-Hamid in favour of a settlement which should include the evacuation of Egypt, and an English alliance against Russia with Turkey, Persia and Afghanistan.” This resulted in Sultan Abdul Hamid supposedly inviting Afghani to Turkey himself, but would rather spell out the Masonic plans for Afghani in Turkey who influenced it’s Tanzimat reforms, and helped establish opposition to the Khalifah with the founding of the Young Turks movement not long after, that replaced it all together.

The following accounts are taken entirely from the research conducted by the University of Wisconsin which is based mainly on recently discovered documents and other primary sources.

The research paper traces Afghani’s connections with Freemasonry and concludes that he attempted to use the Mason’s as a ready-made agency for political mobilization and agitation against the ruler of Egypt, Khedive Isma’il. Many of his followers, such as Muhammad ‘Abduh, Sa’d Zaghlul, Ya’qib Sannu’ and Adib Ishaq, joined the Masons, as did notables, army officers, and Isma’il’s son, Tawfiq Pasha. Disagreement between some lesser Masonic factions who did not want to get involved in politics resulted in Afghani’s formation of a “national” lodge above all other lodges, this indicated the degree of his influence and power, and from where he continued his agitation until he was expelled in August of 1879.

When Afghani arrived in Egypt in March 1871, he was given a government pension and began teaching philosophy at al-Azhar, Islam’s highest institution. Opposition from the traditional ulama (scholars) to Afghani’s reformist ideas forced him to withdraw from the mosque-university, but he continued to meet with a few students at his home. His following increased and the topics discussed in the almost daily gatherings dealt increasingly with social and political issues. By the time he was expelled in 1879 he was actively engaged in political agitation.

In the greater context of Egypt without a Khalifah Afghani preached the isolation of Egypt from the rest of the Muslim world, His divide and conquer motives would be achieved by arousing the ideas of nationalism in his followers knowing entirely that nationalism was condemned in the Quran and Sunnah, the prophet (saws) explicitly stating he came to abolish nationalism along with the racism and the classes it created.

Afghani lived in an age when Nationalism was first introduced to the world in order to divide people into increasingly smaller groups and replace their heritage, he and the Salafi Muslim Brotherhood were some of the tools used to achieve this aim by foreign powers.

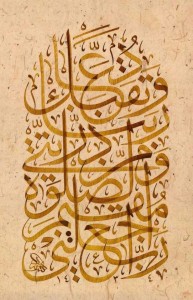

“And verily this Ummah (nation) of yours is a single Ummah and I am your Lord and Cherisher: Therefore Fear Me.”(23:53)

“But people have cut off their affair (of unity), between them into sects: Each party rejoices in that which is with itself.” (30:12)

The Messenger of Allah (saws) said, “He is not one us who calls for nationalism or who fights for nationalism or who dies for nationalism.” (Abu Dawwud)

Muhammad Abduh, referring to the so called illusions Muslims held about the inviolability of the umma (muslim nation) and their dreams of past glory, remarked in the same manner he would employ masonic slogans, that Afghani was particularly interested in “liberating the mind from self-deception” in other words liberating the mind from any opposition to them.

Disagreement occurred between the companions of the prophet (saws), Abu Dharr and Bilal, and Abu Dharr said to Bilal, “You son of a black woman.” The Messenger of Allah (saws) was extremely upset by Abu Dharr’s comment, so he (saws) rebuked him by saying, “That is too much, Abu Dharr. He who has a white mother has no advantage which makes him better than the son of a black mother.” This rebuke had a profound effect on Abu Dharr, who then put his head on the ground swearing that he would not raise it until Bilal put his foot over it.

This statement of Muhammad Abduh outlines the entire aim of Afghani regardless of what his propaganda claimed in front of the masses. If the mind is liberated from one thing it must be replaced by something else because it can not stay empty, it is the nature of man to form attachments because this stabilizes his self and protects him from insanity, it is because of this nature, Allah asks man to attach himself to Haq, the ultimate truths he created in the Universe, and it was to this end the prophet (saws) said “Undoubtedly Allah has removed from you the pride of arrogance of the age of Jahilliyah (ignorance, before Islam) and the glorification of (tribal) ancestors (seen as national heroes). Now people are of two kinds. Either believers who are aware (of what is right and wrong), or transgressors who do wrong (and commit injustice). You are all the children of Adam and Adam was made of clay. People should give up their pride in nations because that is a coal from the coals of Hell-fire. If they do not give this up Allah (swt) will consider them lower than the lowly worm which pushes itself through dung.”

Afghani liberated peoples minds from “this reality”, and attached it to his temporary goals through slogans and short sighted idealism that ultimately only achieved his aim.

Ahmad Shafiq adds that he often heard Afghani preach “with courage and candor the fundamental precepts of patriotism,” the rights and duties of citizens, the obligations of rulers toward their subjects, the responsibility of governmental officials for their actions and the principle of justice under law…as if Islam had not been the one to establish these things 1400 years earlier, the underlaying context to everything He said was the isolation of Egypt from the rest of the Islamic world.

It was through such slogans and blind idealism that Afghani would move people away from one ideology just so they can embrace another. One look at Islam’s legal history will show that the modern legal system is almost entirely indebted to the sciences developed by Islam’s scholars none less so then it’s founding of the principles of jurisprudence, regarding which the prophet (saws) said about it’s founder, Imam Shafii, “O Allah! Guide (the tribe of) Quraysh, for the science of the scholar that comes from them will encompass the earth. O Allah! You have let the first of them taste bitterness, so let the latter of them taste reward.”

Afghani grew increasingly critical of Ismail’s policies this disaffection was first voiced in secret, and mainly Masonic societies. By 1879—the year of Ismail’s deposition—it had become an open campaign.

Freemasonry was introduced into Egypt in 1798 by officers of the invading French army, under the rule of Muhammad Ali several lodges were founded under the jurisdiction of the Grand Orient of France. By the 1860s, a host of chapters were formed under the jurisdiction of a variety of Rites: French, English, Scottish, Italian, German and Greek, eight lodges were founded between 1862 and 1868 under the United Grand Lodge of England alone.

Although all of these were presumably started by European residents, many of them included Egyptian intellectuals, professionals and notables. Most important and influential among these was Prince ‘Abd al-Halim Pasha, Muhammad Ali’s youngest son, who in 1867 was elected Grand Master of the Order of the Grand Orient of Egypt.

Some Italian chapters, for instance, harbored conspirators against the Italian Royal House and underworld criminals. In terms of Egyptian politics, Freemasonry offered a ready-made organization for those interested in subversive activities against the Khedive Isma’il. Two personalities who utilized the Masons for this purpose were Afghani and ‘Abd al-Halim. The latter, who felt swindled when Isma’il obtained the Sultan’s approval to replace the Ottoman law of succession (where the oldest living male member of the ruling family inherits the throne) with primogeniture, used his Masonic connections without success in directing anti-Isma’il propaganda both in Egypt and in exile.

Afghani himself kept few records and any kept by the lodges have not yet come to light, except for a group of recently discovered papers belonging to Afghani. Along with numerous contemporary reports, these have now been pieced together and the following description of the nature and scope of Afghani’s covert activities in Egypt made clear.

Afghani’s earliest known contact with the Masons is a letter dated May, 1875 requesting his admission into one of the lodges in Cairo. The letter does not reveal the name of the lodge, but its identity is not vital since Afghani soon belonged to several lodges. Other documents show that he was invited to attend sessions in various lodges until he left Egypt. Among these were the Italian Luce d’Oriente, Nilo and Mazzini. It would appear that at least between 1877 and 1879 he belonged to one or more of these, because the invitations he received concerned the election of new members and memorial services for past members. In other documents he is identified as a member of the Nile lodge of Cairo which was affiliated with the National Grand Lodge of Egypt (one of three Grand Masonic bodies established in May, 1878 when the French Grand Orient was reorganized).

Afghani was also a leading member of the Star of the East (Kawkab al-Sharq), his member number was 1355, it was founded in Cairo in 1871 and affiliated with the United Grand Lodge of England. According to Mohammed Sabry, it was the British Vice-Consul in Cairo, Raphael Borg, himself a Mason, who urged Afghani and his followers through this chapter.

Soon it had many members from the Egyptian elite, including Tawflq Pasha (Ismail’s son), Sharif Pasha, Butrus Pasha Ghall, Sulayman Pasha ‘Abaza, Muhammad “Abduh, Sa’d Zaghlul, army officers like Latif Bey Salim and Sa’id Nasr, members of the Assembly of Delegates and even ‘ulama’ (so called scholars).

The following January 1878, just a year after joining he was elected president of the lodge, indicating his vast connections and competency with the occult.

Another document is an invitation, dated 3 February, 1879, asking Afghani to attend a meeting at the “Greek lodge of Cairo” Finally, a letter written in Paris in March, 1884 indicates that Afghani applied for membership in one of the local chapters when he was residing in the French capital.

Masonic lodges were eminently suited for the covert activities he wished to advocate. They provided the machinery for organized agitation against Isma’il’s policies. In these efforts, Afghani was aided by some of his own disciples whom he persuaded to join the Mason’s. Muhammad Abduh would join, and in 1875, the Jewish Egyptian nationalist Ya’qub Sannu’ became a Mason, later Sa’d Zaghlul, ‘Abd al-Salam al-Muwaylihl, Adlb Ishaq, Sallm al-Naqqash and Ibrahim al-Laqqanl were also initiated.

Afghani’s efforts to politicize his fellow Egyptian Masons were initially opposed by those not used to such activities. Eventually, Afghani withdrew from the lodge and formed another lodge under his own leadership. Afghani did so after he “realized that he could not work with those brothers while they were in this state of indifference, fear and cowardice.”

Another account was given by Rashid Rida, the student of Muhammad Abduh. Basing his story on information from ‘Abduh, he states that “the initial cause for the withdrawal of Afghani and ‘Abduh was an incident which took place during a visit to Egypt by the English Grand Master, the Prince of Wales. The Masonic lodges honored the visitor lavishly and when one of the leading members addressed him as Crown Prince, Afghani objected that it was not permissible to address any member as such (members having to leave their status at the door) “even though he was the heir to the British Empire”, his symbolic objections to the prince may account for his future allegiances. Furthermore, the British government had not conferred any favors upon the lodge yet. Some of the leaders, however, repudiated these statements and after a debate, Afghani withdrew along with a select group of followers.

The Star of the East lodge was affiliated with the United Grand Lodge of England. He was installed as head in January, 1878, while the rupture between the English and French Masons had taken place in 1877. Moreover, he was a member of the Nile lodge at least as late as August, 1878, “as its model”, this lodge “follows the

Several accounts report that following his withdrawal from the English Masons, Afghani formed “a national lodge” (mafyfalan wataniyyan) affiliated with the French Grand Orient, although after his exile from Egypt, and while in France, his affiliations would change back, visiting England and accepting assignments from them. Within a short time this lodge boasted a membership of more than three hundred. Besides Afghani’s usual followers, it attracted a number of journalists, intellectuals, notables, ‘ulama’ (scholars), members of the Assembly and some army officers.

The members were divided into several committees to serve as liaisons with government departments. One was entrusted with the War Minister, others were assigned to the Ministers of Justice, Finance, Public Works, etc.

It was through this association remarks Rashid Rida, that ‘Abduh was able to establish contact with Tawfiq Pasha and other leaders of Egypt. Tawfiq’s association with Afghani can be traced to this period. He joined the lodge headed by Afghani, and at his inauguration as Khedive leader of Egypt on 27 June, 1879, a delegation of Masons from this lodge went to congratulate him. Also, when he died in 1892, another delegation was present at the funeral ceremonies.

On his part, Tawfiq professed liberalism and promised constitutional reforms upon his accession to the Khedivate. Whether he was privy to any plot to remove his father by force can only be conjectured, but certainly Afghani was thinking in these terms. ‘Abduh relates that in the spring of 1879 Afghani and many notables asked the then Chief Minister Sharif Pasha to “convince Isma’il of the need to abdicate” but Isma’il refused. Later Afghani led a delegation of Egyptians to see the newly arrived French Consul-General, Tricou, and told him that “there is in Egypt a national party which wants reform…and that this reform cannot be carried out except at the hands of the heir-apparent Tawfiq Pasha.”

In this we see, the now french masons, making efforts to place in power a ruler in Egypt loyal to them, it would not be long after the struggle between these groups that the English Empire would come to colonize Egypt outright.

There was much private talk in that spring among a group of Azhari reformers influenced by Afghani as to how Isma’il could be deposed; they even considered assassination, much as did the Salafi Muslim Brotherhood years later, assassinating one Egyptian president and attempting to kill another.

In ‘Abduh’s words, Afghani proposed that Isma’il should be assassinated as he passed in his carriage daily over the Kasr el Nil bridge, and I strongly approved, but it was only talk between ourselves, and we lacked a person capable of taking a lead in the affair.

Afghani, a Times correspondent observed, had “almost obtained the weight of a Median law among the lower and less educated classes” meaning his rule, even the king was powerless to change, the lower classes would come to form the Salafi movement and eventually the Muslim Brotherhood.

It was during these turbulent times that the national movement began to emerge. In April, 1879 the existence of the Patriotic (Party) Society (al-Hizb al-Watani) became publicly known.

When Tawfiq replaced his father as Khedive in June, 1879, Afghani was no longer his main teacher, he would come into contact with less corrupt Muslims working in the government.

Afghani and the nationalists still believed that the long-awaited reforms could at last be instituted, for such had been the impression given by Tawfiq before his accession. He continued to give the same impression during the first few weeks of his reign. For example, the delegation of Masons sent to congratulate him upon his accession was assured of his intention to implement reforms. Sharif Pasha, who had been serving as Chief Minister since April, stayed in office holding the same notion. Afghani, too, remained on good terms. But the honeymoon did not last long. Afghani, Sharif and the various nationalist groups were applying pressure on Tawfiq for immediate reforms.

Sharif submitted a plan for a constitution that would have created a strong representative assembly and ministerial responsibility, but at the expense of the Khedive’s powers, Tawfiq’s foreign consuls advised him otherwise, replacing Sharif with Riyad.

Supported by Sherif Pasha, he [Afghani] for some time deemed it expedient to conceal his more pronounced views, but on the fall of the late Ministry [of Sharif] he seems to have lent himself more openly to a propaganda against the introduction of the European element in any form into the administration of the country, possibly demonstrating the point he turned back to British Masonry.

Afghani now disillusioned not knowing who his allies were, a French journalist gives the following eyewitness account: One evening in the Hasan mosque in Cairo, before an audience of four thousand people, he [Afghani] gave a powerful speech in which he (duplicitly) denounced with a deep prophetic sense, three years before the event, the ultimate purpose of British policy on the banks of the Nile. He also showed at the same time the Khedive Taufiq as compelled to serve—consciously or not— British ambitions, and ended his speech by a war-cry against the foreigner and by a call for a revolution to save the independence of Egypt and establish liberty.

It would not be long after this that the British Empire would have the pretext it needed to colonize Egypt and control the Suez Canal along with all traffic through it, Two World Wars would later prove how vital this area was.

At the same time, Afghani was implicated in a plot attributed to the Masonic followers of ‘Abd al-Halim, the son of Muhamad Ali the former ruler of Egypt, aimed at replacing Tawfiq with Halim. In letters written in 1883, Afghani complained that it was the officer ‘Uthman Pasha (the Police Chief of Cairo) who had spread these malicious rumors and told Tawfiq that Afghani planned to kill him in concert with the Masons.

To Riyad Pasha he wrote: “A group of foreign Masons and their followers… who were under the leadership of ‘Abd al-Halim when he was president of the Masonic Order in Cairo, tried to work for Halim’s succession and I, out of my love for the Khedive Tawfiq, left them.”

On the 24 August, 1879, Afghani was seized by the police, whisked away to Suez, and was put on a ship bound for India. A few days later the official gazette, al-Waqa’i’ al-Misriyya, published the government’s statement, and new independent stance, charging Afghani with leading a secret society based on violence, and as it was revealed nearly 2000 years earlier to the companion John (ra) who would likewise state, “aimed at corrupting religion and the world”.